I found two reviews of the book I co-authored. The first one is below, which I posted before. It’s so interesting to find reviews instead of having reviewers let you know of them. Never would have known except for a search for something related to ADHD that led to this review awhile back and the other a few weeks ago.

I found two reviews of the book I co-authored. The first one is below, which I posted before. It’s so interesting to find reviews instead of having reviewers let you know of them. Never would have known except for a search for something related to ADHD that led to this review awhile back and the other a few weeks ago.

Book Review:

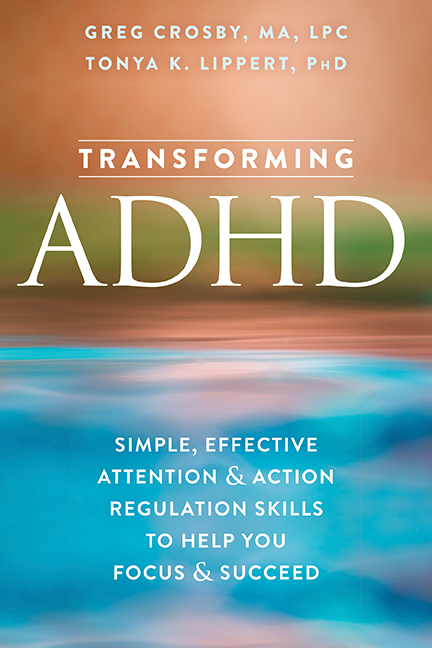

Transforming ADHD

ADHD is not as it sounds — an attention deficit disorder.

According to the authors of Transforming ADHD: Simple, Effective Attention & Action Regulation Skills To Help You Focus & Succeed, Greg Crosby, MA, LPC, and Tonya K. Lippert, PhD, ADHD is a difficulty regulating and adjusting attention to fit the situation you are in.

Guided by the interdisciplinary approach known as interpersonal neurobiology, Crosby and Lippert show that ADHD is about much more than simply learning to pay attention. It is about successfully navigating and recognizing the external and internal environments that influence attention.

“The biggest confusion about ADHD seems to stem from its reference to a ‘deficit.’ As ADHD scholar Hallowell and Ratey (2005) said to refer to an attention deficit when speaking of the experience of ADHD ‘completely misses the point’,” write Crosby and Lippert.

According to the authors, attention is biased — that is, it moves toward some things and away from others. For those with ADHD, it’s not that attention itself but the flexibility or control of attention that is lacking. The result of this low attention regulation, is not just over-focusing and under-focusing; it also effects how we sustain effort and manage emotions.

One biochemical reason people with ADHD may have difficulty paying attention to what is not exciting is because they have lower levels of dopamine. Low dopamine function in turn leads to behaviors that seek to compensate for dopamine deficiency.

Crosby and Lippert offer helpful tips for those with ADHD to learn to place their attention where they want. Learning what they call the four S’s of attention – starting, sustaining, stopping, and shifting – can be helpful. Next, by paying attention to what activities attract and detract attention, and pairing activities of low interest with those of high interest, those with ADHD can practice sustaining attention when it might otherwise wander.

A person’s environment can also have a significant impact on his or her ability to pay attention, according to the authors. They write that part of becoming successful with ADHD involves designing your environment for optimal attention and action regulation.

“When it comes to long-term goals, (designing your exterior environment to work with your interior environment) means introducing representations of your desired future into your present by, for example, taping pictures of your desired home on your computer screen if your impulsive purchases occur online,” write Crosby and Lippert.

They also offer some other examples of environmental design such as closing yourself into a room where you are less accessible to the dog, wearing headphones, working away from home or taping an assignment list to the side of your computer monitor.

Another practice, which Crosby and Lippert call Introduce Results of Tomorrow Today (IRTT) helps those with ADHD overcome urges that draw attention away from the long term results they want.

Crosby and Lippert tell the story of Zelda, who had tried and failed to quit cigarettes many times. It wasn’t until she made a pact with a close friend that if she smoked she’d have to give $5000 to the KKK that Zelda was able to quite for good. This practice is a powerful way to maintain personal accountability, and also to learn that with a little effort, it is possible to design an environment that improves attention and action regulation.

Those with ADHD can also adopt healthy behavior to change not just attention and action regulation, but the gene expression related to them – which is called epigenetics. Crosby and Lippert cite one study where exercise was shown to affect the gene expression within cells throughout the body – brain, heart, bone, muscle, mouth and fat – including directly altering fat formation. One helpful brain exercise the authors recommend: Replace multi-tasking with mindful-tasking.

Understanding relationships and the neurobiology between them is also important in managing ADHD. One important reason, the authors write, is that people with ADHD have higher rates of insecure attachment as children, which predisposes them to poor self-regulation.

While we can’t rewrite our childhoods, what we can do is better understand our attachment patterns (for which the authors offer a helpful quiz) and then shift to security through reflecting on our childhood and practicing mindfulness.

Learning to communicate more effectively is also fundamental for people with ADHD. The authors suggest practicing mindful listening, paraphrasing, and what they call “urge surfing” or learning to notice — but not respond to — urges within a conversation.

“When you surf an urge, including the urge to interrupt, you notice the urge without acting on it. It’s an action regulation skill — a way to stop an action,” they write.

Packed with useful and effective exercises, Transforming ADHD offers a fresh and insightful look at ADHD – and one that might just change your life.

s. A supplement heavier on the omega-3 than omega-6 side may be better, as indicated by a study that found benefit from giving participants an omega-3/6 supplement containing mostly EPA and DHA (omega-3), with only 60mg of LA (omega-6).

s. A supplement heavier on the omega-3 than omega-6 side may be better, as indicated by a study that found benefit from giving participants an omega-3/6 supplement containing mostly EPA and DHA (omega-3), with only 60mg of LA (omega-6).

t reading this, you likely do, too. And I will admit, I’m torn.

t reading this, you likely do, too. And I will admit, I’m torn.

ault mode network”). Without ADHD, when one network has its turn to be active, the other one turns down…they cooperate. With ADHD, they appear to often be active at the same time. Imagine what that’s like. If you have ADHD, you already know. If only others could experience your brain to know what it’s like….

ault mode network”). Without ADHD, when one network has its turn to be active, the other one turns down…they cooperate. With ADHD, they appear to often be active at the same time. Imagine what that’s like. If you have ADHD, you already know. If only others could experience your brain to know what it’s like….

Children often say it best.

Children often say it best.