This is an overview of ADHD (Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder), primarily numbers and names.

123s…

What’s the prevalence? It’s estimated to be about 5-6% of the world population of children and 3-4% of the world population of adults (using DSM-IV criteria, DSM-5 criteria increase the estimates slightly). It’s estimated that about 1-2% of children without childhood ADHD may meet criteria for ADHD after 12 years of age. This suggests that about half of the population of adults with ADHD develop it “late.”

123s and ABCs…

When did the first formal description of ADHD appear, albeit under a different name? One best guess is 1798 by Alexander Crichton. Dr. Faraone at SUNY Upstate Medical University suggests it goes back even farther…to Weikard and a 1775 German medical textbook. See https://adhdinadults.com/a-brief-history-of-adhd/

Fast forward to 1968, when it became an official diagnosis here (the U.S.), being added to the DSM-II, clinicians’ reference for diagnoses of mental disorders. It was called Hyperkinetic Disorder of Childhood. The name changed over the years but the essence of the disorder as one of childhood hyperactivity, impulsivity and wayward attention remained.

In 1980, the DSM-III came out and added specifics to the diagnosis, such as indicating that symptoms had to appear before 7 years of age. There was no research showing that 7 was a magic number; only enough clinicians believing this made sense.

In 1994, the DSM-IV softened the age of onset “rules” requiring only some of the symptoms to appear before age 7. Subtypes were also added. It was during the 1990s that Adult ADHD became recognized as a valid disorder.

In 2013, the DSM-5 changed the requirement that symptoms be present before age 7 to before age 12.

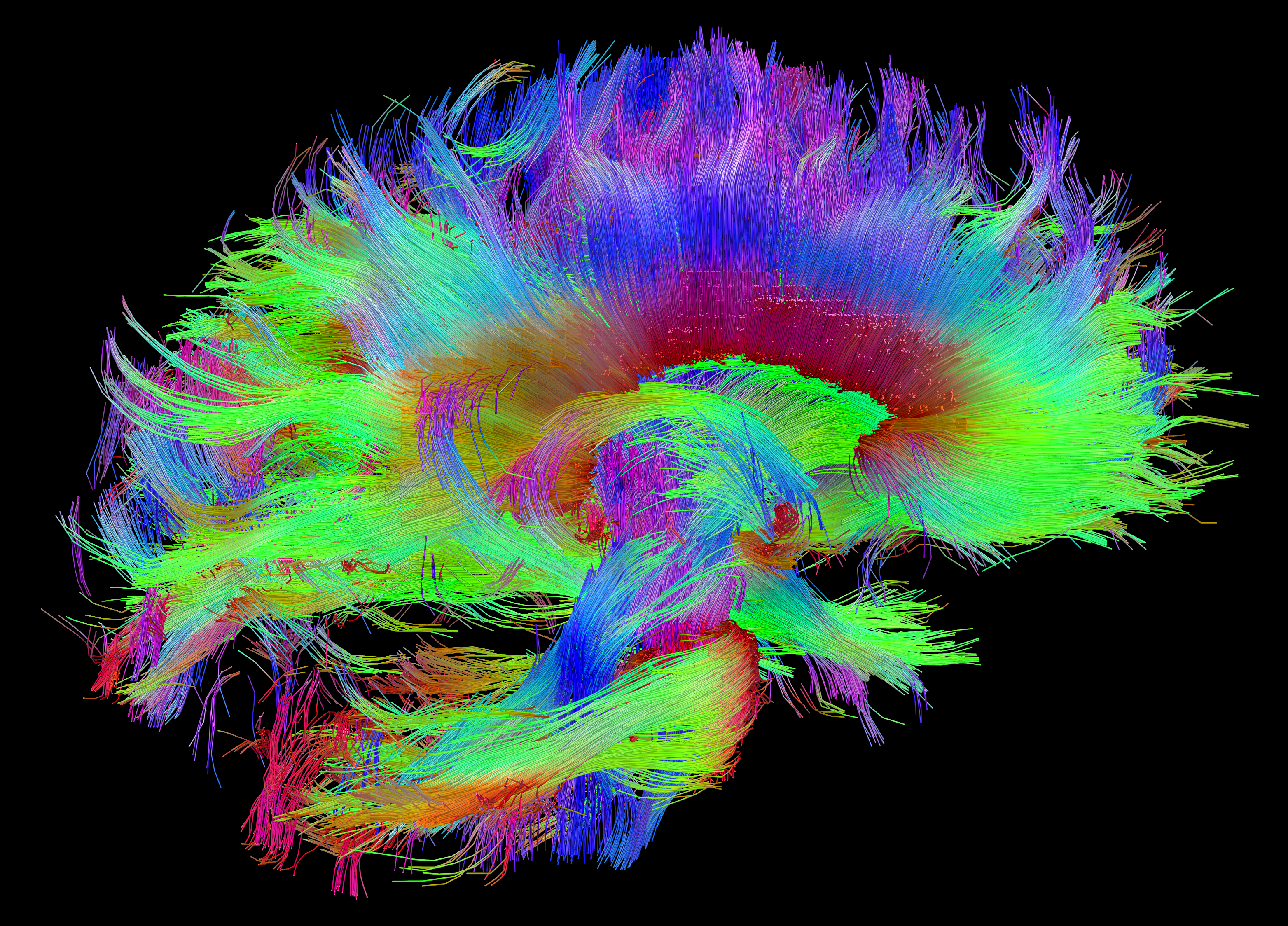

WHAT IS IT? ADHD is a self-regulation disorder. Regulation is, essentially, flexible self-control described by 4 Ss: starting, sustaining, stopping and switching attention, action, motivation, and more. It is understood as a neurodevelopmental disorder, which is to say it is a way that the brain (“neuro”) develops that affects, more than anything, self-regulation, essentially, decreasing it compared to what’s seen for those without ADHD. And here’s the disorder part: It is associated with distress and/or dysfunction, including poorer results at school and work, higher levels of health-risking behaviors, and being less satisfied with oneself.

What Causes It? It’s believed to result from certain combinations of genes and environmental factors. Genes are believed to be necessary and… insufficient. So are environmental factors. This means you need both.

Sources:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=annual+research+review+does+late-onset+attention-deficit

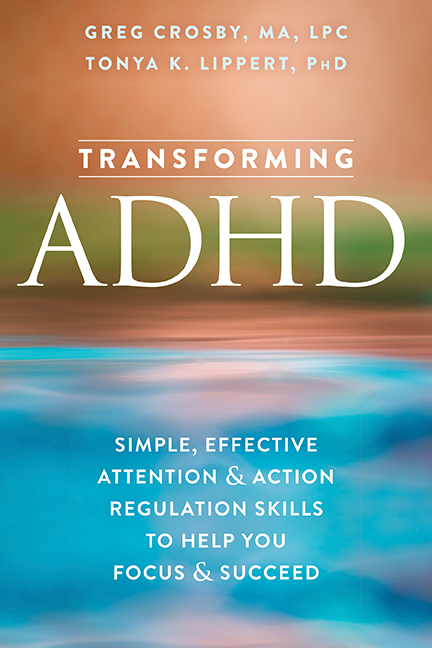

I found two reviews of the book I co-authored. The first one is below, which I posted before. It’s so interesting to find reviews instead of having reviewers let you know of them. Never would have known except for a search for something related to ADHD that led to this review awhile back and the other a few weeks ago.

I found two reviews of the book I co-authored. The first one is below, which I posted before. It’s so interesting to find reviews instead of having reviewers let you know of them. Never would have known except for a search for something related to ADHD that led to this review awhile back and the other a few weeks ago.